Church Responsive Readings in Ecclesiastes, Chapter 1

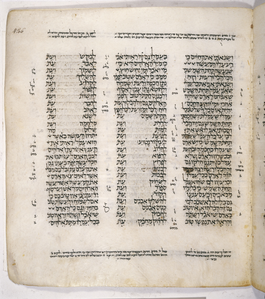

Ecclesiastes (; Hebrew: קֹהֶלֶת , qōheleṯ , Aboriginal Greek: Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs ) written c. 450–200 BCE, is one of the Ketuvim ("Writings") of the Hebrew Bible and ane of the "Wisdom" books of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly used in English language is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew give-and-take קֹהֶלֶת ( Kohelet, Koheleth, Qoheleth or Qohelet ). An unnamed author introduces "The words of Kohelet, son of David, rex in Jerusalem" (one:1) and does not apply his own vocalisation again until the final verses (12:9-14), where he gives his own thoughts and summarises the statements of "Kohelet"; the principal trunk of the text is ascribed to Kohelet himself.

Kohelet proclaims (1:2) "Vanity of vanities! All is futile!"; the Hebrew discussion hevel , "vapor", tin can figuratively mean "insubstantial", "vain", "futile", or "meaningless". Given this, the next poetry presents the basic existential question with which the rest of the volume is concerned: "What turn a profit hath a man for all his toil, in which he toils nether the sun?", expressing that the lives of both wise and foolish people all terminate in decease. While Kohelet endorses wisdom as a means for a well-lived earthly life, he is unable to ascribe eternal meaning to it. In light of this perceived senselessness, he suggests that human beings should enjoy the simple pleasures of daily life, such equally eating, drinking, and taking enjoyment in one's work, which are gifts from the mitt of God. The volume concludes with the injunction to "Fear God and keep his commandments; for that is the all of mankind. Since every deed will God bring to judgment, for every hidden act, be it good or evil".

Championship [edit]

'Ecclesiastes' is a phonetic transliteration of the Greek word Ἐκκλησιαστής ( 'Ekklesiastes' ), which in the Septuagint translates the Hebrew proper noun of its stated author, Kohelet ( קֹהֶלֶת ). The Greek word derives from ekklesia (assembly),[1] as the Hebrew give-and-take derives from kahal (assembly),[2] but while the Greek word means 'member of an assembly',[three] the significant of the original Hebrew discussion information technology translates is less sure.[4] As Strong's cyclopedia mentions,[5] information technology is a female person agile participle of the verb kahal in its simple ( qal ) paradigm, a form not used elsewhere in the Bible and which is sometimes understood as agile or passive depending on the verb,[a] so that Kohelet would mean '(female) assembler' in the active case (recorded as such past Strong's concordance),[5] and '(female) assembled, member of an assembly' in the passive case (as per the Septuagint translators). According to the majority agreement today,[4] the give-and-take is a more than general ( mishkal , קוֹטֶלֶת ) form rather than a literal participle, and the intended meaning of Kohelet in the text is 'someone speaking before an assembly', hence 'Teacher' or 'Preacher'.

Structure [edit]

Ecclesiastes is presented as the biography of "Kohelet" or "Qoheleth"; his story is framed by the voice of the narrator, who refers to Kohelet in the third person, praises his wisdom, merely reminds the reader that wisdom has its limitations and is not human being'south main concern.[half dozen] Kohelet reports what he planned, did, experienced and thought, but his journey to noesis is, in the end, incomplete; the reader is not merely to hear Kohelet's wisdom, simply to observe his journey towards understanding and acceptance of life's frustrations and uncertainties: the journey itself is important.[vii]

Few of the many attempts to uncover an underlying structure to Ecclesiastes have met with widespread acceptance; amidst them, the following is i of the more than influential:[8]

- Title (1:1)

- Initial poem (1:2–11)

- I: Kohelet's investigation of life (1:12–6:ix)

- II: Kohelet's conclusions (half-dozen:10–11:half-dozen)

- Introduction (vi:x–12)

- A: Man cannot discover what is skillful for him to exercise (vii:one–8:17)

- B: Human being does not know what will come after him (9:1–eleven:6)

- Concluding poem (xi:7–12:8)

- Epilogue (12:9–fourteen)

Despite the credence by some of this structure, there have been many criticisms, such equally that of Flim-flam: "[Addison Yard. Wright's] proposed structure has no more than effect on estimation than a ghost in the cranium. A literary or rhetorical structure should non merely 'be there'; information technology must practice something. Information technology should guide readers in recognizing and remembering the author's train of thought."[9]

Poetry i:1 is a superscription, the ancient equivalent of a title page: it introduces the book every bit "the words of Kohelet, son of David, rex in Jerusalem."[x]

Almost, though not all, modern commentators regard the epilogue (12:ix–14) as an addition by a later scribe. Some have identified certain other statements every bit further additions intended to make the book more religiously orthodox (eastward.g., the affirmations of God's justice and the need for piety).[11]

It has been proposed that the text is equanimous of three singled-out voices. The first belongs to Qoheleth as the prophet, the "true vox of wisdom",[12] which speaks in the start person, recounting wisdom through his own feel. The second vox belongs to Qoheleth equally the king of Jerusalem, who is more didactic and thus speaks primarily in second-person imperative statements. The third phonation is that of the epilogist, who speaks proverbially in the third person. The epilogist is most identified in the book's showtime and final verses. Kyle R. Greenwood suggests that following this construction, Ecclesiastes should exist read as a dialogue between these voices.[12]

Summary [edit]

The ten-poetry introduction in verses 1:ii–11 are the words of the frame narrator; they set the mood for what is to follow. Kohelet'south bulletin is that all is meaningless.[x]

After the introduction come up the words of Kohelet. Equally king, he has experienced everything and done everything, but concludes that cipher is ultimately reliable, equally death levels all. Kohelet states that the only expert is to partake of life in the present, for enjoyment is from the manus of God. Everything is ordered in fourth dimension and people are subject field to fourth dimension in dissimilarity to God's eternal character. The world is filled with injustice, which just God volition adjudicate. God and humans do non belong in the same realm, and it is therefore necessary to accept a right mental attitude before God. People should enjoy, simply should not be greedy; no-one knows what is skillful for humanity; righteousness and wisdom escape humanity. Kohelet reflects on the limits of human power: all people confront death, and death is better than life, only people should enjoy life when they can. The globe is full of risk: he gives advice on living with risk, both political and economic. Mortals should take pleasure when they can, for a time may come when no i tin. Kohelet'due south words finish with imagery of nature languishing and humanity marching to the grave.[13]

The frame narrator returns with an epilogue: the words of the wise are hard, but they are applied as the shepherd applies goads and pricks to his flock. The ending of the book sums upward its message: "Fright God and proceed his commandments for God will bring every deed to judgement."[14] Some scholars suggest 12:13-xiv were an addition past a more orthodox writer than the original writer;[15] [16] others think it is likely the work of the original writer.[17]

Limerick [edit]

[edit]

Colorized version of Rex Solomon in Old Age by Gustave Doré (1866); a delineation of the purported author of Ecclesiastes, according to rabbinic tradition.

The book takes its proper name from the Greek ekklesiastes , a translation of the title past which the central figure refers to himself: 'Kohelet', meaning something like "i who convenes or addresses an assembly".[18] Co-ordinate to rabbinic tradition, Ecclesiastes was written past Solomon in his onetime age[19] (an alternative tradition that "Hezekiah and his colleagues wrote Isaiah, Proverbs, the Vocal of Songs and Ecclesiastes" probably means simply that the book was edited nether Hezekiah),[xx] just critical scholars have long rejected the idea of a pre-exilic origin.[21] [22] Co-ordinate to Christian tradition the book was probably written by another Solomon, Gregory of Nyssa wrote that information technology was written by some other Solomon,[23] for Didymus the Blind that it was probably written by several authors.[24] The presence of Persian loanwords and Aramaisms points to a date no earlier than near 450 BCE,[half-dozen] while the latest possible engagement for its composition is 180 BCE, when the Jewish author Ben Sira quotes from it.[25] The dispute as to whether Ecclesiastes belongs to the Persian or the Hellenistic periods (i.eastward., the earlier or subsequently part of this menstruum) revolves around the caste of Hellenization (influence of Greek civilization and thought) nowadays in the book. Scholars arguing for a Persian date (c. 450–330 BCE) concord that there is a complete lack of Greek influence;[6] those who fence for a Hellenistic date (c. 330–180 BCE) argue that information technology shows internal bear witness of Greek thought and social setting.[26]

Also unresolved is whether the author and narrator of Kohelet are one and the same person. Ecclesiastes regularly switches between tertiary-person quotations of Kohelet and first-person reflections on Kohelet's words, which would indicate the book was written every bit a commentary on Kohelet'southward parables rather than a personally-authored repository of his sayings. Some scholars have argued that the tertiary-person narrative structure is an artificial literary device along the lines of Uncle Remus, although the description of the Kohelet in 12:eight–14 seems to favour a historical person whose thoughts are presented by the narrator.[27] The question, withal, has no theological importance,[27] and one scholar (Roland White potato) has commented that Kohelet himself would have regarded the time and ingenuity put into interpreting his volume as "one more example of the futility of human being effort".[28]

Genre and setting [edit]

Ecclesiastes has taken its literary form from the Middle Eastern tradition of the fictional autobiography, in which a graphic symbol, often a king, relates his experiences and draws lessons from them, ofttimes self-critical: Kohelet too identifies himself as a king, speaks of his search for wisdom, relates his conclusions, and recognises his limitations.[7] The book belongs to the category of wisdom literature, the body of biblical writings which give advice on life, together with reflections on its problems and meanings—other examples include the Book of Task, Proverbs, and some of the Psalms. Ecclesiastes differs from the other biblical Wisdom books in beingness deeply skeptical of the usefulness of wisdom itself.[29] Ecclesiastes in turn influenced the deuterocanonical works, Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach, both of which incorporate vocal rejections of the Ecclesiastical philosophy of futility.

Wisdom was a popular genre in the ancient world, where information technology was cultivated in scribal circles and directed towards immature men who would take upwards careers in loftier officialdom and royal courts; there is strong evidence that some of these books, or at least sayings and teachings, were translated into Hebrew and influenced the Book of Proverbs, and the author of Ecclesiastes was probably familiar with examples from Arab republic of egypt and Mesopotamia.[30] He may also have been influenced past Greek philosophy, specifically the schools of Stoicism, which held that all things are fated, and Epicureanism, which held that happiness was all-time pursued through the quiet cultivation of life's simpler pleasures.[31]

Canonicity [edit]

The presence of Ecclesiastes in the Bible is something of a puzzle, as the common themes of the Hebrew canon—a God who reveals and redeems, who elects and cares for a called people—are absent from information technology, which suggests that Kohelet had lost his organized religion in his old historic period. Understanding the book was a topic of the primeval recorded discussions (the hypothetical Council of Jamnia in the 1st century CE). One statement advanced at that time was that the proper noun of Solomon carried enough authorization to ensure its inclusion; however, other works which appeared with Solomon'south name were excluded despite beingness more orthodox than Ecclesiastes.[32] Some other was that the words of the epilogue, in which the reader is told to fear God and go along his commands, made information technology orthodox; but all later attempts to find annihilation in the residuum of the volume that would reflect this orthodoxy have failed. A modern suggestion treats the book as a dialogue in which different statements vest to unlike voices, with Kohelet himself answering and refuting unorthodox opinions, but there are no explicit markers for this in the book, equally at that place are (for example) in the Book of Job.

Yet another suggestion is that Ecclesiastes is simply the most farthermost example of a tradition of skepticism, but none of the proposed examples friction match Ecclesiastes for a sustained denial of faith and doubt in the goodness of God. Martin A. Shields, in his 2006 book The End of Wisdom: A Reappraisal of the Historical and Canonical Role of Ecclesiastes, summarized that "In short, we do not know why or how this book found its way into such esteemed company".[33]

Themes [edit]

Scholars disagree virtually the themes of Ecclesiastes: whether it is positive and life-affirming, or deeply pessimistic;[34] whether information technology is coherent or incoherent, insightful or confused, orthodox or heterodox; whether the ultimate message of the book is to copy Kohelet, the wise human, or to avoid his errors.[35] At times Kohelet raises deep questions; he "doubted every attribute of religion, from the very platonic of righteousness, to the past now traditional idea of divine justice for individuals".[36] Some passages of Ecclesiastes seem to contradict other portions of the Old Testament, and even itself.[34] The Talmud fifty-fifty suggests that the rabbis considered censoring Ecclesiastes due to its seeming contradictions.[37] One suggestion for resolving the contradictions is to read the volume as the record of Kohelet'south quest for knowledge: opposing judgments (due east.g., "the dead are better off than the living" (four:ii) vs. "a living dog is better off than a dead lion" (ix:four)) are therefore provisional, and information technology is merely at the conclusion that the verdict is delivered (11–12:7). On this reading, Kohelet'southward sayings are goads, designed to provoke dialogue and reflection in his readers, rather than to achieve premature and self-assured conclusions.[38]

The subjects of Ecclesiastes are the pain and frustration engendered by observing and meditating on the distortions and inequities pervading the world, the uselessness of homo appetite, and the limitations of worldly wisdom and righteousness. The phrase "nether the sun" appears twenty-nine times in connectedness with these observations; all this coexists with a firm belief in God, whose ability, justice and unpredictability are sovereign.[39] History and nature move in cycles, then that all events are predictable and unchangeable, and life, without the sunday, has no meaning or purpose: the wise man and the man who does non study wisdom will both die and be forgotten: human being should be reverent ("Fear God"), only in this life information technology is all-time to just savour God'due south gifts.[31]

Judaism [edit]

In Judaism, Ecclesiastes is read either on Shemini Atzeret (by Yemenites, Italians, some Sepharadim, and the mediaeval French Jewish rite) or on the Shabbat of the Intermediate Days of Sukkot (by Ashkenazim). If there is no Intermediate Sabbath of Sukkot, Ashkenazim besides read information technology on Shemini Atzeret (or, in Israel, on the first Shabbat of Sukkot). It is read on Sukkot as a reminder not to go also caught upward in the festivities of the holiday, and to acquit over the happiness of Sukkot to the rest of the year by telling the listeners that, without God, life is meaningless.

The last poem of Kohelet[twoscore] has been interpreted in the Targum, Talmud and Midrash, and by the rabbis Rashi, Rashbam and ibn Ezra, as an allegory of old age.

Catholicism [edit]

Ecclesiastes has been cited in the writings of past and current Catholic Church building leaders. For example, doctors of the Church have cited Ecclesiastes. St. Augustine of Hippo cited Ecclesiastes in Volume Twenty of Metropolis of God.[41] Saint Jerome wrote a commentary on Ecclesiastes.[42] St. Thomas Aquinas cited Ecclesiastes ("The number of fools is space.") in his Summa Theologica .[43]

The 20th-century Catholic theologian and central-elect Hans Urs von Balthasar discusses Ecclesiastes in his work on theological aesthetics, The Celebrity of the Lord. He describes Qoheleth every bit "a critical transcendentalist avant la lettre ", whose God is distant from the world, and whose kairos is a "grade of time which is itself empty of meaning". For Balthasar, the role of Ecclesiastes in the Biblical canon is to represent the "final dance on the part of wisdom, [the] conclusion of the ways of man", a logical end-signal to the unfolding of homo wisdom in the Quondam Testament that paves the way for the advent of the New.[44]

The book continues to be cited by recent popes, including Pope John Paul 2 and Pope Francis. Pope John Paul II, in his general audience of October 20, 2004, chosen the author of Ecclesiastes "an ancient biblical sage" whose description of death "makes frantic clinging to earthly things completely pointless."[45] Pope Francis cited Ecclesiastes on his address on September 9, 2014. Speaking of vain people, he said, "How many Christians alive for appearances? Their life seems like a soap chimera."[46]

Influence on Western literature [edit]

Ecclesiastes has had a deep influence on Western literature. Information technology contains several phrases that accept resonated in British and American culture, such as "consume, drink and be merry", "nothing new nether the sun", "a time to be born and a fourth dimension to dice", and "vanity of vanities; all is vanity".[47] American novelist Thomas Wolfe wrote: "[O]f all I have ever seen or learned, that book seems to me the noblest, the wisest, and the nigh powerful expression of human being's life upon this world—and as well the highest flower of poetry, eloquence, and truth. I am non given to dogmatic judgments in the thing of literary creation, but if I had to brand one I could say that Ecclesiastes is the greatest single slice of writing I have ever known, and the wisdom expressed in it the near lasting and profound."[48]

- The opening of William Shakespeare's Sonnet 59 references Ecclesiastes ane:9–10.

- Line 23 of T. S. Eliot'due south "The Waste product Land" alludes to Ecclesiastes 12:5.

- Christina Rossetti's "Ane Certainty" quotes from Ecclesiastes 1:2–ix.

- Leo Tolstoy's Confession describes how the reading of Ecclesiastes affected his life.

- Robert Burns' "Address to the Unco Guid" begins with a verse entreatment to Ecclesiastes 7:16.

- The title of Ernest Hemingway'southward commencement novel The Sunday Besides Rises comes from Ecclesiastes one:5.

- The title of Edith Wharton'due south novel The House of Mirth was taken from Ecclesiastes vii:4 ("The eye of the wise is in the firm of mourning; but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth.").

- The title of Laura Lippman's novel Every Hugger-mugger Thing and that of its pic accommodation come from Ecclesiastes 12:14 ("For God shall bring every piece of work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it exist evil.").

- The master character in George Bernard Shaw'south short story The Adventures of the Blackness Daughter in Her Search for God [49] meets Koheleth, "known to many equally Ecclesiastes".

- The title and theme of George R. Stewart'southward post-apocalyptic novel Earth Abides is from Ecclesiastes 1:4.

- In the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury's master graphic symbol, Montag, memorizes much of Ecclesiastes and Revelation in a earth where books are forbidden and burned.

- Pete Seeger's song "Plough! Turn! Turn!" takes all but one of its lines from the Volume of Ecclesiastes chapter 3.

- The passage in affiliate 3, with its repetition of "A time to ..." has been used equally a title in many other cases, including the novels A Time to Dance by Melvyn Bragg and A Fourth dimension to Impale by John Grisham, the records ...And a Time to Dance past Los Lobos and A Time to Love by Stevie Wonder, and films A Time to Love and a Fourth dimension to Die, A Time to Alive and A Time to Kill.

- The opening quote in the moving picture Platoon by Oliver Stone is taken from Ecclesiastes 11:ix.

- The essay "Politics and the English Language" by George Orwell uses Ecclesiastes 9:eleven as an example of clear and vivid writing, and "translates" it into "mod English of the worst sort" to demonstrate common fallings of the latter.

See as well [edit]

- Bible

- Q, novel by Luther Blissett

- A Rose for Ecclesiastes

- Tanakh

- "Turn! Turn! Turn!"

- Vanitas

- Vier ernste Gesänge

- Wisdom of Sirach

- The Song

Notes [edit]

- ^ As opposed to the hifil form, always active 'to assemble', and niphal class, always passive 'to exist assembled' - both forms often used in the Bible.

Citations [edit]

- ^ "Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu . Retrieved 2020-07-28 .

- ^ "Strong'south Hebrew: 6951. קָהָל (qahal) -- associates, convocation, congregation". biblehub.com . Retrieved 2020-07-29 .

- ^ "Greek Give-and-take Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu . Retrieved 2020-07-28 .

- ^ a b Even-Shoshan, Avraham (2003). Even-Shoshan Dictionary. pp. Entry "קֹהֶלֶת".

- ^ a b "H6953 קהלת - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon". studybible.info . Retrieved 2020-07-28 .

- ^ a b c Seow 2007, p. 944.

- ^ a b Play tricks 2004, p. thirteen.

- ^ Flim-flam 2004, p. xvi.

- ^ Play tricks 2004, p. 148-149.

- ^ a b Longman 1998, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Fox 2004, p. xvii.

- ^ a b GREENWOOD, KYLE R. (2012). "Debating Wisdom: The Part of Phonation in Ecclesiastes". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 74 (iii): 476–491. ISSN 0008-7912. JSTOR 43727985.

- ^ Seow 2007, pp. 946–57.

- ^ Seow 2007, pp. 957–58.

- ^ Ross, Allen P.; Shepherd, Jerry E.; Schwab, George (7 March 2017). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Vocal of Songs. Zondervan Academic. p. 448. ISBN978-0-310-53185-two.

- ^ Change, Robert (2018-12-18). The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (Vol. Three-Volume Set). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN978-0-393-29250-3.

- ^ Weeks 2007, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Gilbert 2009, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Brown 2011, p. eleven.

- ^ Smith 2007, p. 692.

- ^ Fox 2004, p. x.

- ^ Bartholomew 2009, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Wright 2014, p. 287.

- ^ Wright 2014, p. 192.

- ^ Fob 2004, p. xiv.

- ^ Bartholomew 2009, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Bartholomew 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Ingram 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Brettler 2007, p. 721.

- ^ Fox 2004, pp. x–xi.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Diderot, Denis (1752). "Canon". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert - Collaborative Translation Project: 601–04. hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.566.

- ^ Shields 2006, pp. 1–5.

- ^ a b Bartholomew 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Enns 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Hecht, Jennifer Michael (2003). Incertitude: A History. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 75. ISBN978-0-06-009795-0.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 30b. sfn mistake: no target: CITEREFBabylonian_Talmud_Shabbat_30b (assistance)

- ^ Brown 2011, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Fox 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Ecclesiastes 12:1–8

- ^ Augustine. "Book 20". The City of God.

- ^ Jerome. Commentary on Ecclesiastes.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica.

- ^ von Balthasar, Hans Urs (1991). The Glory of the Lord. Volume VI: Theology: The Former Covenant. Translated past Brian McNeil and Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 137–43.

- ^ Manhardt, Laurie (2009). Come and Run across: Wisdom of the Bible. Emmaus Road Publishing. p. 115. ISBN9781931018555.

- ^ Pope Francis. "Pope Francis: Vain Christians are like soap bubbles". Radio Vatican . Retrieved 2015-09-09 .

- ^ Hirsch, E.D. (2002). The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. eight. ISBN0618226478.

- ^ Christianson 2007, p. lxx.

- ^ Shaw, Bernard (2006). The adventures of the blackness girl in her search for God. London: Hesperus. ISBN1843914220. OCLC 65469757.

References [edit]

- Bartholomew, Craig G. (2009). Ecclesiastes. Baker Bookish. ISBN9780801026911.

- Wright, Robert. (2014). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon. ISBN978-0830897346.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2007). "The Poetical and Wisdom Books". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible (3rd ed.). Oxford Academy Press. ISBN9780195288803.

- Brown, William P. (2011). Ecclesiastes: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN9780664238247.

- Christianson, Eric S. (2007). Ecclesiastes Through the Centuries. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN9780631225294.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2008). The Onetime Testament: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9780199719464.

- Diderot, Denis (1752). "Canon". The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Susan Emanuel (2006). hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.566. Trans. of "Catechism",Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. ii. Paris, 1752.

- Eaton, Michael (2009). Ecclesiastes: An Introduction and Commentary. IVP Academic. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-01-07 .

- Enns, Peter (2011). Ecclesiastes. Eerdmans. ISBN9780802866493.

- Fredericks, Daniel C.; Estes, Daniel J. (2010). Ecclesiastes & the Song of Songs. IVP Bookish. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-01-07 .

- Fox, Michael V. (2004). The JPS Bible Commentary: Ecclesiastes. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN9780827609655.

- Gilbert, Christopher (2009). A Consummate Introduction to the Bible: A Literary and Historical Introduction to the Bible. Paulist Printing. ISBN9780809145522.

- Hecht, Jennifer Michael (2003). Doubt: A History. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-009795-0.

- Ingram, Doug (2006). Ambiguity in Ecclesiastes. Continuum. ISBN9780567027115.

- Krüger, Thomas (2004). Qohelet: A Commentary. Fortress. ISBN9780800660369.

- Longman, Tremper (1998). The Book of Ecclesiastes. Eerdmans. ISBN9780802823663.

- Ricasoli, Corinna, ed. (2018). The Living Dead: Ecclesiastes through Art. Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 9783506732767.

- Rudman, Dominic (2001). Determinism in the Book of Ecclesiastes. Sheffield Bookish Printing. ISBN9780567215635.

- Seow, C.L. (2007). "Ecclesiastes". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN9780195288803.

- Shields, Martin A. (2006). The End of Wisdom: A Reappraisal of the Historical and Canonical Role of Ecclesiastes. Eisenbrauns. ISBN9781575061023.

- Smith, James (1996). The Wisdom Literature and Psalms. College Press. ISBN9780899004396.

- Smith, James E. (August 2007). The Wisdom Literature and Psalms. Higher Printing. ISBN978-0-89900-954-iv.

- Weeks, Stuart (25 January 2007). Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-927718-half dozen.

External links [edit]

- Kohelet – Ecclesiastes (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi'south commentary] at Chabad.org

- Ecclesiastes: New Revised Standard Version

- Ecclesiastes: Douay Rheims Bible Version

- Ecclesiastes at Wikisource (Authorised Male monarch James Version)

- Ecclesiastes at United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (New American Bible)

- Ecclesiastes at Bible Gateway (New King James Version)

- A Metaphrase of the Volume Of Ecclesiastes by Gregory Thaumaturgus.

-

Ecclesiastes public domain audiobook at LibriVox – Various versions

Ecclesiastes public domain audiobook at LibriVox – Various versions

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecclesiastes

0 Response to "Church Responsive Readings in Ecclesiastes, Chapter 1"

Post a Comment